By JERUSALEM POST STAFF

Dr. Christopher Monk insists the appendage is 'the missing penis', while George Garnett argues it's a weapon's sheath.

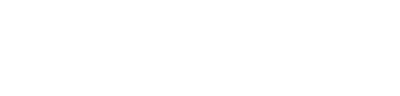

A renewed scholarly debate emerged over the exact number of phalluses depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, the famous medieval embroidery over 70 meters long that illustrates the events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. According to The Guardian, George Garnett, a professor at Oxford University, identified 88 phalluses linked to horses and five attached to humans, bringing his total count to 93. However, Christopher Monk, an expert in Anglo-Saxon nudity, claimed there is actually a 94th phallus, pointing to a previously overlooked detail beneath a running man.

"I'm in no doubt that the appendage is a depiction of male genitalia—the missed penis, shall we say? The detail is surprisingly anatomically fulsome," said Monk, according to The Guardian. Garnett, on the other hand, is convinced that the object is the sheath of a sword or a dagger. "The object Dr. Monk identified as a penis is actually a sword or scabbard dangling beneath the man's legs," said Garnett.

The two historians recently engaged in a discussion on the HistoryExtra podcast, where they debated the nature of this ambiguous detail in the tapestry. Both scholars emphasized that their work, despite the humorous subject matter, is far from frivolous. "What I've shown is that this is a serious, learned attempt to comment on the conquest—albeit in code," Garnett said. "Studying history is about understanding how people thought in the past."

Monk explained his reasoning behind identifying the 94th phallus. "Some of the stitches appear to be original: the pale thread of the circular testicles and possibly the tip, or glans, are so; the black stitches of the shaft are, though, later restoration," he observed. He also consulted medieval embroidery expert Alexandra Makin about the nature of the stitching. "Their observations corroborate each other, though neither is saying the appendage is a depiction of male genitals," Monk noted. "That's my own interpretation of the stitches which, as I've implied, depict all the necessary parts—a penis, with its distinct glans, and two testicles."

The debate not only focuses on the count of phalluses but also on their significance within the tapestry's narrative. Garnett believes that the unknown designer of the Bayeux Tapestry was highly educated and used literary allusions to subvert the standard story of the Norman conquest. "We know the designer was learned—he was using Phaedrus's first-century Latin translation of Aesop's fables, rather than some vague folk tradition," he stated.

Garnett pointed out that the two leaders of the Battle of Hastings—Harold Godwinson, who died at Hastings from an arrow in his eye, and Duke William of Normandy, also known as William the Conqueror—are depicted on horses with noticeably larger penises. "William's horse has by far the largest penis. And that's not a coincidence," he asserted. According to Garnett, size was indeed important in the tapestry, symbolizing the power and status of the commanders.

The scholars agree that the inclusion of explicit details in the Bayeux Tapestry serves a purpose beyond mere decoration. "Instead of being random crude additions, the depictions of nudity in the Bayeux Tapestry are making a point. Sexual activity is involved, or shame, and that makes me think that the designer is covertly alluding to betrayal," Garnett explained.

David Musgrove, host of the HistoryExtra podcast and a Bayeux Tapestry expert, commented on the debate. "It's a reminder that this embroidery is a multi-layered artefact that rewards careful study and remains a wondrous enigma almost a millennium after it was stitched," he said.